Abstract

Roman Jakobson categorizes translation work into three dimensions named intralingual, interlingual and intersemiotic. The third one includes the idea of film adaptation based on a literary text. But there is no appropriate censor of determining how much liberty one screenwriter can enjoy in converting the source text into film. The discussion deserves a particular attention if we consider Satyajit Ray’s Ganashatru, a film based on Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People. In the film, Ray has added a lot of new elements and brought about a lot of changes. In particular, the film ends with a realization of Dr. Ashok Gupta that he is not alone at all while The Enemy of the People ends with the admiration of loneliness. As Ray changes one of the most striking themes of Ibsen’s text, the comparison between the source text and the film becomes significant in regards of translation. The present study throws light on the transformation of Dr. Stockmann to Dr. Ashok Gupta with all his surroundings including culture, time as well as history and an approach on how Ray’s Ganashatru handles the gap between two distinct cultures and time-frames. It also includes an analysis on how Ganashatru with all its changes from the source text has become an excellent intersemiotic translation to the audience of the Indian subcontinent.

Key words: Ganashatru, Intersemiotic Translation, An Enemy of the People, Culture

Translation generally establishes the relationship between two particular languages. As it is based on bilingualism, it obviously brings about the issue of foreignness and cultural

aspects. Communication between the source language and the target language is a major factor in this regard. From Roman Jakobson’s point of view, translation can take place between two particular languages, within the same language and between two systems of signs. Jakobson names the last system of translation as intersemiotic translation and defines it as “an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (233). It includes the transformation of particular structure of signs into another distinct configuration. It basically relates the conversion of a literary text into film, music, painting etc. When a film is made based on a literary text, it becomes a finished product and the assessments centering round the film hardly invite the ground of the transformation process. Unfortunately, we do not have more studies which would focus on the process of separating a literary text from its offspring.

Translation is actually a sort of transformation which not only brings two languages, but also two distinct cultural systems closer. The idea of faithfulness in this regard relates the consciousness of the translator that he must put emphasis on the contents of the source text rather than the aim of the author. It is, in fact, a relative issue and always determined by the translator’s clever implementation of a particular cultural system in his/her target text. For example, Shakespeare’s sonnet “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day” cannot be semantically translated into a language where summers are unpleasant, just as the concept of God the Father cannot be translated into a language where the deity is female (Bassnett 30). Suresh Ranjan Basak’s translation of Shakespeare’s sonnet “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day” can be cited in this regard:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate

বসন্ত দিনের সাথে মানায় কি তোমার তুলনা?

তার চেয়ে ঢের বেশী সুমধুর, মনোহর তুমি।. (12)

Summer in Bangladesh cannot be matched with the summer in England. Shakespeare finds this pleasing season to show his readers that his friend is more pleasing than even the charms of English summer. Basak must have realized that the literal meaning of summer would not serve the purpose of the poet’s thought and eventually, changed ‘summer’ into ‘spring’ for Bangladeshi readers. To determine whether an intersemiotic translation is successful is a very difficult task as it depends on some particular strategies adopted in the target texts. Octavio Paz claims:

Every text is unique and, at the same time, it is the translation of another text. No text is entirely original because language itself, in its essence, is already a translation: firstly, of the non-verbal world and secondly, since every sign and every phrase is the translation of another sign and another phrase. (qtd. in Bassnett 44)

Interdisciplinary study has been appreciated by the scholars for decades. It has emphasized on translation studies which involves new approaches for examining the confusing and conflicting variables emerging from theses texts. In this regard, Torop likes to see ‘translation’ as a mixture of cultural, psychological and ideological activities. He suggests a particular model where he stresses on not only study methods of translation but also the study method of the translator. He conceptualizes ‘intersemiotic translation’ as ‘total translation’ on the ground of textual ontology. He says: “Co-existence of the verbal and the visual and non-coincidence of their border and the border between the verbal and iconic . . . points to the productivity of a semiotic approach both in textology and in the analysis of texts of culture” (280). It is evident that to Torop, intersemiotic translation is equivalent to the study of cultural communication. On this ground, film adaptation can be seen as intersemiotic translation though its success depends on the skill of the translator regarding the transfer of the particular sign –systems and cultural aspects.

The idea of intersemiotic translation is one of the most problematic issues in translation studies considering the gap between two or more semiotic codes or between linguistic text-signs and nonlinguistic codes. In case of changing the code from the stage to the film or from the book to the screen, there is no censor which determines how loyal one screenwriter or director should be towards the source text. As an intersemiotic translator, one must take care of the particular cultural system in which he intends to re-create it. S/he must not avoid his or her loyalty towards it including its cultural and political history and time-frame.

Jakobson claimed that the meaning of a sign is its translation into another sign or

sequence of signs in the same language, in another language or in another semiotic (e.g., visual) language. Following Jakobson, Itamar Even-Zohar (1990a, 1997) elaborated a theory of transfer, which applies to all variations of the following phenomenon: a text which was created in a cultural system A is re-created in a cultural system B. Even-Zohar’s theory of transfer, rooted in his polysystem theory, has been used in research dealing with transfer within one language (Shavit 1986) and from literature to the cinema (Cattrysse 1992; Remael 2000). (qtd in Weissbrod 42)

Any discussion of the relationship between the source text and the recreated audiovisual text demands a primary objection: the autonomous sense inherent in each text. A lot of issues work in such a way that the texts are not interchangeable. To establish the concept of intersemiotic translation, the social, cultural, religious and historical discourses are important to think about. For the target-text readers, cultural aspects should be skillfully handled by the translator.

We find that Ibsen’s play got originated in Norwegian cultural system in 19th century. Naturally he used his own individual thought coupled with contemporary views and complications. In the then Norway, most of the people lived in towns and for each town, the dwellers had a Mayor who led them in different aspects. They also had the printing media, and other public services like public bath. In local politics in Norway, as Ibsen shows in his play, the majority always exercised power over minority. Ibsen observed how the minority struggled to uphold their rights and how the majority ruled them with tyranny. In the then Norwegian society, money and power were the things that never got away from politics as in An Enemy of the People the Mayor wants his power; he doesn’t want his brother’s discovery to disturb his power in the city. Eventually Dr. Stockman, the protagonist of the play becomes an enemy of the people. His patients abandon him and his daughter is fired from her job. His first reaction is to take his wife and children away from the town. But as the mob breaks his windows, he decides to stay and try to re-educate the townspeople with his new found discovery. Ibsen admires this loneliness:

- STOCKMANN: Are you quite mad, Katrina! Drive me out! Now that I am the strongest man in the town?

MRS. STOCKMANN: The strongest—now?

- STOCKMANN: Yes, I venture to say this: that now I am one of the strongest men in the world.

MORTENN: I say, what fun!

- STOCKMANN (in a subdued voice): Hush; you mustn’t speak about it yet; But I have made a great discovery.

MRS. STOCKMANN: What, another?

- STOCKMANN: Yes, of course (Gathers them about him, and speaks confidently): This is what I have discovered, you see: the strongest man in the world is he who stands most alone.

MRS. STOCKMANN (shaking her head, smiling): Ah, Thomas dear—!

PETRA (grasping his hands cheeringly): Father! (77)

Though at the end of the play Dr. Stockmann is at war with society, he feels he is the strongest man in the society despite of the fact that he is alone. But Ray has to place the story and theme in Indian culture. He is aware of the demand of the Indian tradition and history linked with it. For him, money, politics and some moral issues are not enough to turn ‘a friend’ into ‘a public enemy’. He sets Ganashatru in Chandipur, a small town in Bengal which has recently drawn the visitors’ attention for being a health resort. Dr. Stockmann in An Enemy of the People has become Dr. Ashok Gupta in Ganashatru. Dr. Gupta works as the head of a hospital which is run by a trust founded by a local businessman, Bhargava. Ashok Gupta’s brother Nisith Gupta is a powerful man in the town and the chief of the hospital committee. There is a temple in the town which works as the accelerator to turn Ibsen’s play into an Indian film. Somehow the temple’s water supply gets infected for some substandard pipes and eventually, there is an outbreak of jaundice. The affected people are identified to be the frequenters to the temple. Laboratory tests in Kolkata verify the doubt of Dr. Gupta as fact. Now, a strong sense of enmity gets built up between Dr. Gupta and Bhargava accompanied by Nisith centering round Dr Gupta’s finding. Bhargava, like many other Hindus, accepts as true that holy water (charanamrita) cannot be impure as it contains Ganges water, tulsi leaves and sacred basil leaves. The local newspaper editor at first realizes the fact but eventually goes against Dr. Gupta. Dr. Gupta calls for a public meeting at a hall to make the people understand the matter but it also goes against Dr. Gupta because of the political strategies engineered by Nisith Gupta. The film, however, ends with a slogan of the young educated people of the area who declare that they are in favour of Dr. Gupta. This optimistic note is one of the most significant changes that Ray brings in Ganashatru.

Ray is particularly influenced by his own cultural forces and the role of the youth in the history of Bengal. If Ray presented Dr Ashok Gupta as a man in the desolate state at the end of the day, it would be a sheer injustice to the spirited youth in Bengal. The audience of the Indian subcontinent is not ready to see the youth playing a silent role to stand beside the cultural and religious reformists. Ray keeps faith in youth to protect his protagonist Dr Gupta. One example can be cited here to understand Ray’s view on the youth of his contemporary time. At the very beginning of Pratiwandi (Ray’s another film, based on a novel of Sunil Gangopadhhay), there is a conversation between Siddharth, the protagonist of the film and the interviewer in a job interview:

Interviewer: What is the most significant event in the last decade?

Siddharth: The war in Vietnam.

Interviewer: Do you consider this more significant than the moon-landing?

Siddharth: Yes, I do. (Ray 1972)

The Bengali speaking people must keep in mind the role of the youth in the language movement of 1952 in Pakistan. Besides, the youth of the Bengal played the most significant role in the Liberation war of India and that of Bangladesh. History says that they never remained silent in religious, cultural or political crisis. Though Ray’s movies are enjoyed and applauded by the people around the world, the audience is particularly the Bengali speaking people. Edward Sapir opines:

No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached. (qtd in Bassnett 21)

The audience of Ganashatru finds Dr. Ashok Gupta, the protagonist of the film, in a completely different state, literally far away from the denouement of Ibsen’s play. Dr. Gupta says:

I am not alone, Maya, I am not alone… I have a lot of friends. I will stay here, I have to work here. (Ray 1989) (Author’s translation)

In Ganashatru, the two other significant features are a little magazine and a theatre group. It is important to note here that in the history of any cultural revolution in this region, these two always played a striking role. Ray doesn’t forget about the Young Bengal Movement and its founder Henry Louis Vivian Derozio who spent only 22 years on the earth but during his life time, he constantly persuaded the other young people around him to think freely, to inquire and not to believe anything blindly. Though he went against the wind, he got a lot of young people beside him. His thoughts and inspiration gave birth to the development of the spirit of freedom and equality among the people. Even in Charulata, Vupati (one of the central characters in the film) is portrayed as the follower of Derozio. Such young people of Hindu college also published Parthenon, a revolutionary little magazine inspiring liberalism in thought. These historical truths lead Ray to add few elements to Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People. The first one is Moshal, a little magazine and the second one is a theatre group consisting of the same group of young people who are involved in the publication of Moshal. At the end of the film, all the members of the group come to help Ashok Gupta; they stand beside him and this is how Dr Stockmann transforms into Ashok Gupta to the audience of the Indian subcontinent. He also becomes firmed as Dr. Stockmann but the source of Dr Stockmann’s firmness is his realization about the strength of the truth even in the state of isolation. Ashok Gupta doesn’t admire loneliness and even doesn’t think himself unaccompanied.

Moreover, Ray adds another element to identify the role the youth in this respect and it is the proof of Dr. Gupta’s article. Its significance is marked with a young couple, Indrani and Romen who love each other. They talk to each other just for once in the film but their conversation isn’t confined to the expression of their love for each other or any other familial issue. They discuss with each other regarding the editing of the proof. This is very important to understand the thoughts of the youth or how Ray wants to see them. This symbol again returns in the last scene of Ganashatru. When the doctor is at the peak of his crisis, Romen appears with this very proof of the article in his hand. He gets relieved a little bit realizing that it is the editor of a little magazine who dare publish his essay, not the editor of a renowned daily. This is how the proof has become the symbol of a historical truth about the youth in the Bengal.

But as Dr. Gupta is about to sink in despair, his daughter, her friend, and local students take up the fight. No, all is not lost. One can still live. One can still communicate, one can still be creative. (Roberge 95)

Ray also adds a slogan to his script. As soon as the doctor takes the proof in his hand, he hears the slogan of the theatre people supporting him. The slogan has such strength in it that it provides the doctor with a platform and a truth that he is not alone at the end of the day. Ray is, in fact, very conscious about the changes:

I have to bring some changes in the story of the source text due to its time and context. I have added a ray of hope at the very end of Ganashatru but after all, I don’t think the script or the film may hamper recognizing Ibsen. (Ray 212) (Author’s translation)

If we compare this ending with the denouement of An Enemy of the People, the origin of the difference between these two becomes transparent and this is nothing but Ray’s awareness about the history, time-frame and culture in which he lives in. Roberge in his Satyajit Ray mentions about an article of Charles Tesson where he says:

. . . that collusion of politics and poetics in a same voice is really a miracle, and it is beautiful that people whose life is committed to art, to representation, in the end occupy the field of politics. (qtd in Roberge 96)

The camera of Ganashatru moves round some selected places only—the residence of Dr Ashok Gupta, the premise of the temple, the local newspaper office and a hall and these places are portrayed as disconnected from the outside world to some extent. So, the audience may have a chance to explore a sense of theatrical flavour in the film but Ray uses three techniques to hold his film upright—(1) the in-depth presentation of the characters, (2) the intensity of story analysis and (3) the condensed style of preparing scenes and editing.

As the source text is a play, Ray has to take special care of the dialogues. The significant thing is that Ganashatru is based on the dialogues but not burdened with dialogues. He uses ‘close-up’ shots to use the lengthy dialogues of the characters. The techniques Ray uses here are the slow movement of the camera, presenting the inner significance of the scenes and the long ‘close-ups’. Roberge in his Satyajit Ray mentions an interview of Ray which was reproduced by William Fisher in an issue of Cahiers du Cinema and here Ray says:

I totally identify with Dr Gupta, an honest man who does not fear the truth. I understand his motivations, his sufferings and his joy at the end. (97)

The challenge Ray faces is that he has to reshape a Norwegian text with Indian flavour. He solves this problem by introducing ‘holy water’ which is linked with Indian culture and religion at its root:

The religious argument, put by the temple owner, Mr Bhargava, rests on the premise that ‘holy water’, by definition, cannot be impure, and that the nature of its essential purity “is beyond the understanding of medical science”. The purity of this ‘holy water’, is ensured by the presence of Ganges water that is regularly added to it along with milk, bel leaves, sesame seeds and, most important of all, tulsi leaves. It is the well-known argument between fundamentalist religion and modern science. (Hood 417)

To make the film an Indian one, he has to depend prominently on religious fundamentalism along with other grounds. The exchange of dialogues between Dr. Gupta and Nisith in the public meeting clearly shows how religious fanaticism and politics work simultaneously to shape the fact in other essences:

Nisith : Have you ever been to the temple?

Dr. Gupta : No, I haven’t. Because I don’t feel the necessity to go there.

Nisith : Do you have any idea how many people drink the holy water every day?

Dr. Gupta : I don’t have a definite idea but I should imagine about seven or eight thousand.

Nisith : How many patients have you had so far?

Dr. Gupta : I am not the only doctor, but I myself have received 200, 250 patients. (Ray, 1989) (Author’s translation)

In An Enemy of the People, Ibsen doesn’t bring the issue of religious formation but Ray knows that the degradation India encounters socially, politically and culturally nowadays gets originated from religious superstitions:

It is set in 1981, but it is difficult to see the film now without being reminded of controversies in Indian public life that evolved after its release in 1989. In the same year there was a sensation in the Calcutta press as reports came from here and there avowing that idols of the god Ganesh were actually consuming milk. Although the matter was gently derided by most educated people, it made prominent headlines and occupied the media far more than ought to have been warranted by an outburst of silly superstition and hearsay. (Hood 416)

The inner struggle between traditional and modern values in Indian life has coloured several other Ray films. Devi (released in 1960) is essentially a story exploring the dangers of religious fanaticism and superstition.

The film is a dramatized polemic in which the protagonist’s case is clearly stated and then the various arguments against it are put, first by the temple owner, then by the Chairman of the Municipality, then by the press and finally by that characteristically Indian phenomenon, the hired hooligans. (Hood 417)

Ray’s narratology demands the above-mentioned changes and new elements which clear his distinct style of narrative techniques and transmission. Making a film, based on any literary text is not just a concern of placing the dialogues and actions from the pages of a text. In case of novels, the screenwriter gets the narration with its techniques through which s/he can make a sense about the characters with their thoughts, dialogues and actions. The absence of traditional narration makes the task of a screenwriter more complicated in case of a play though the stage direction sometimes plays a significant role in this regard. Literal translation of a literary work is often unacceptable as there must be some distinct differences between two cultural traits and contexts. In films, the director tries to make a sense of parallelism using some specific tools to recreate the text for his/her audience. In this connection, the screenwriter must fulfill the demand of a different medium. Film and play are two different media and each has its own devices to present and manipulate the text. At times, filmmakers bring changes to set up new arguments, accentuate different traits in a character, or even attempt to get to the bottom of problems they pick out in the source text.

Ray’s Ganashatru should not be labeled as merely an ‘adaptation’ because ‘adaptation’ is, in fact, a “ubiquitous phenomenon, but it is not well understood, at least if one insists on the myth of fidelity and denigrate adaptations as se-cond-rate representation (Wu 153). Linda Hutcheon makes a broad discussion which includes that adaptation is not limited to novels and films but an exploration of our hermeneu-tical realms. According to Hutcheon’s view, long-range inadequacies are involved in adaptation. Hutcheon opines that in the Victorian age adaptations included “the stories of poems, novels, plays, operas, paintings, songs, dances, and tab-leaux vivants” (xi), and furthermore that adaptation has permeate our times: “on the television and movie screen, on the musical and dramatic stage, on the Internet, in novels and comic books, in your nearest theme park and video ar-cade” (2). This is not that Ray has been inspired by the play; rather what he has done is that he has translated the text in intersemiotic form. In an interview with the French TV in 1989, Satyajit Ray said:

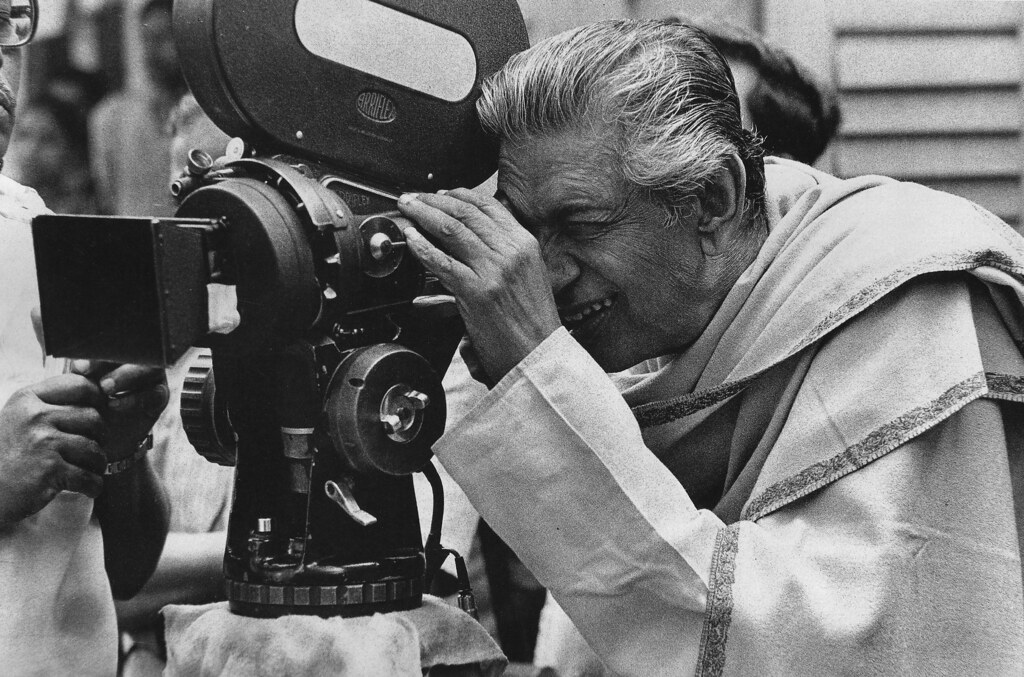

(I re-read) An Enemy of the People because that had stuck in my mind and I admired the character of Dr. Stockman when I read it first in my college. I ….decided to bring it up to date. Completely transplanted to Bengal. (Majumdar 322)

As an intersemiotic translator, Ray enjoys the liberty of bringing changes in cultural settings or themes since the process relates two particular languages along with two particular cultures. Without such changes, the change of the sign systems in another language cannot take place.

An Enemy of the People explores the question of morality and organizational corruption. The people concerned turn a deaf ear to the problems as they intend to avoid moral cues. They keep themselves away from any interest in any further involvement and maintain a safe distance from the matter in question. Such ideas conspicuously exist in Ganashatru; what more Ray shows in his cinematographic version is the explosive issue of religious fanaticism, an issue convincingly relevant in the context of Indian culture. The audience of Ray feels an attachment through the images and sounds which are deeply Indian. Dr. Stockmann’s isolation has tragic glorification but Ray’s Ashok Gupta is out and out an Indian. As an intersemiotic translation it, in fact, addressed the India of 1989 where religious and nationalist intolerance was very much prevalent.

Works Cited

Basak, Suresh Ranjan. Towards Understanding Introduction to Poetry. Dhaka: Dibyaprakash, 2003. Bassnett, Susan. Translation Studies. New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Ganashatru. Dir. Satyajit Ray. Perf. Soumitra Chatterjee, Dhritiman Chatterjee, and Dipankar

Dey. National Film Development Corporation of India Ltd., 1989. You Tube. Web. 28 March 2016.

Hood, John W. Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient

Longman Private Limited, 2008. Print.

Hutcheon, Linda. A theory of adaptation. New York and London: Routledge, 2006. Pdf

Ibsen, Henrik. An Enemy of the People. Ed. Shakti Barta.Delhi: Surjeet Publications, 2004.

Print.

Jakobson, Roman. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” The Translation Studies Readers. Ed. Lawrence Venuti. London: Routlege, 2000. Print.

Majumdar, Indrani. Afterword. Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray. By Marie Seton. New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2003. Print. Munday, Jeremy. Introducing Translation Studies. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Pratiwandi. Dir. Satyajit Ray. Perf. Dhritiman Chatterjee, Mamata Chatterjee, and Krishna

Bose. Priya Films, 1972. You Tube. Web. 28 March 2016

Ray, Satyajit. Prabandha Sangraha. Ed. Sandip Ray. Kolkata: Ananda Publishers Private Limited, 2015

Roberge, Gaston. Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Manohor Publishers & Distributors, 2007. Print.

Torop, Peeter. “Intersemiosis and intersemiotic translation.” Translation translation. Ed. S. Petrilli. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2003. Pdf.

Weissbrod, Rachel. “Inter-Semiotic Translation: Shakespeare on Screen.” Journal of Specialised Translation. 5. (2006): 42-56. Pdf.

Wu, E-Chou. “Intersemiotic Translation and Film Adaptation.” Providence Forum: Language and Humanities 1.8 (2014). 149-182. Pdf